Chapter 6 Version Control

6.1 Introduction

Few software engineers would embark on a new project without using some sort of version control software. Version control software allows us to track the three Ws: Who made Which change, and Why?. Tools like git can be used to track files of any type, but are particularly useful for code in text files for example R or Python code.

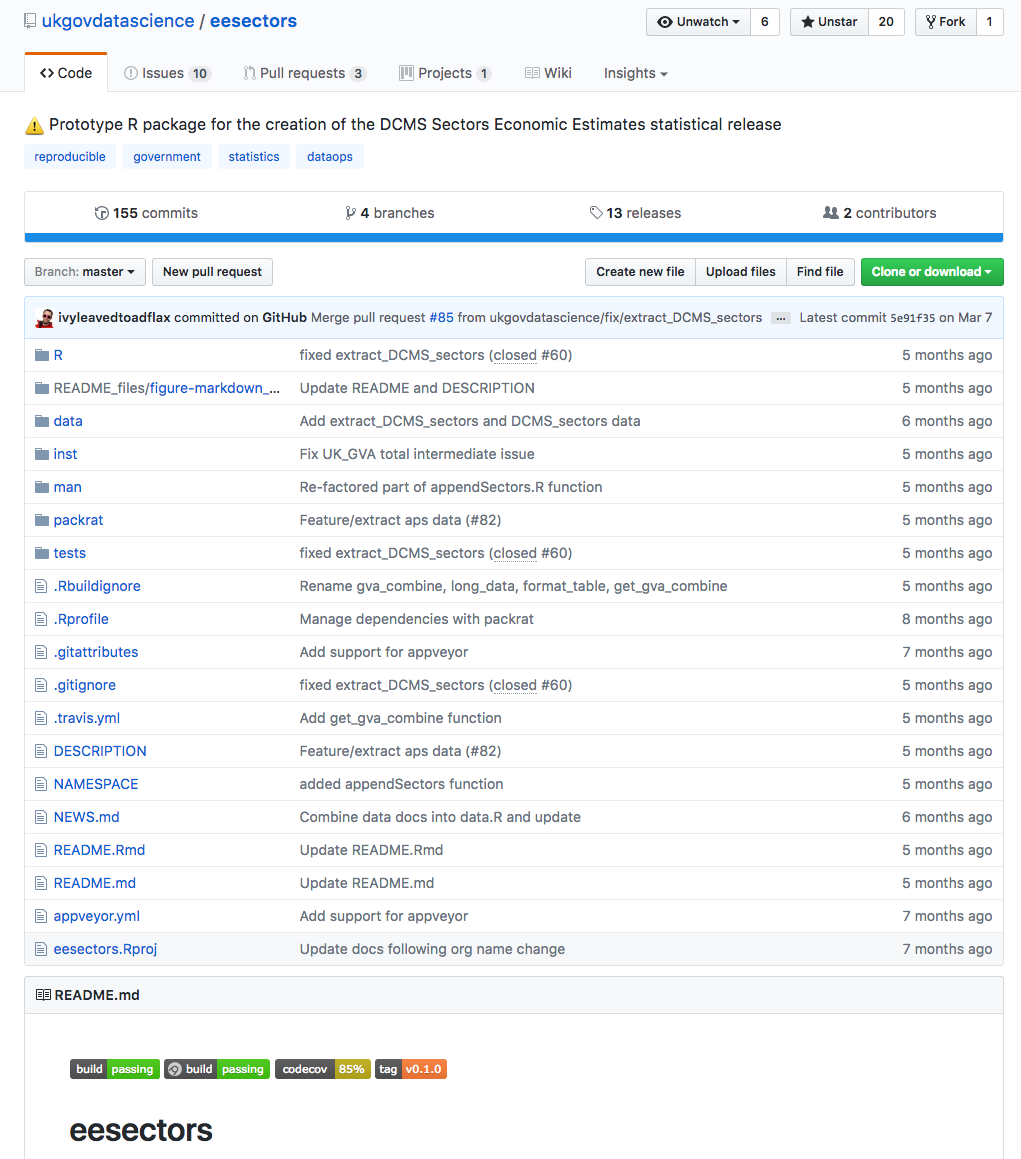

Whilst git can be used locally on a single machine, or many networked machines, git can also be hooked up to free cloud services such as GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket(https://bitbucket.org/). Each of these services provides hosting for your version control repository, and makes the code open and easy to share. The entire project we are working on with DCMS can be seen on GitHub.

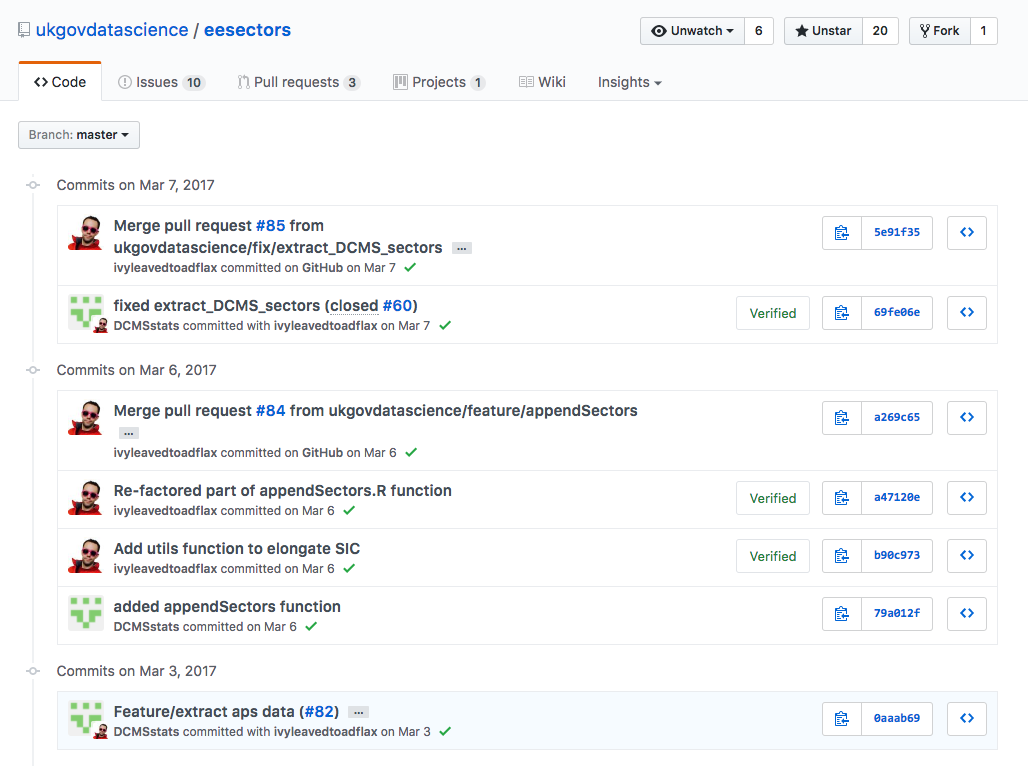

Obviously this won’t be appropriate for all Government projects (and solutions do exist to allow these services to be run within secure systems), but in our work with DCMS, we were able to publish all of our code openly. You can use our code to run an example based on the 2016 publication, but producing the entire publication from end to end would require access to data which is not published openly. Below is a screenshot from the commit history showing collaboration between data scientists in DCMS and GDS. The full page can be seen on GitHub.

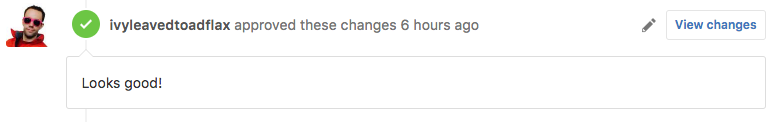

Using a service like GitHub allows us to formalise the system of quality assurance (QA) in an auditable way. We can configure GitHub to require a code review by another person before the update to the code (this is called a pull request) is accepted into the main workstream of the project. You can see this in the screenshot below which relates to a pull request which fixed a minor bug in the prototype. The work to fix it was done by a data scientist at DCMS, and reviewed by a data scientist from GDS.

The open nature of the good is great for transparency and facilitates review. The entire community can contribute to helping QA your code and identify issues or bugs. If you are lucky, they will not only report the bug / issue, but may also offer a fix for your code in the form of a pull request.

6.2 Useful resources

6.2.1 Graphical user interface focus

A useful book on Git and Github that should cover all your needs for those who are uncomfortable working in a command line interface. This will cover most of your Git and Github workflow needs for collaborating in a team. However, we recommend putting the effort into learning git without a GUI, so that you benefit from the full funcitonality on offer.

6.2.2 Git and RStudio

You can also use git and Github within R Studio.

6.2.3 Command line focus

However, the terminal isn’t that scary really and we recommend using it from the outset. Here’s a video tutorial that provides a good introduction and does not expect any experience of using the Unix shell (the terminal or command line).

For a comprehensive tome try the Pro Git book.

6.3 Typical workflow

When you first start using git it can be difficult to remember all the commonly used commands (you might find it useful to keep a list of them in a text editor).

We give a simple workflow here (assuming you are collaborating on Github with a small team and have set up a repo called my_repo with the origin and remote set (try to avoid hyphens in names)). Remember to remove the comments (the #) when copying and pasting into the terminal. You will also need to give your new feature branch a good name.

- Open your terminal (command line tool).

- Navigate to

my_repousingcd. - Check you are up-to-date:

# git checkout master

# git pull- Create your new feature branch to work on and get to work (track changes by adding and comitting locally as usual):

# git checkout -b feature/post_name- Squash your commits if appropriate, then push your new branch to Github. You will want to squash all commits together associated with one discrete piece of work (e.g. coding one function).

# git push origin feature/post_name -uOn Github create a pull request and ask a colleague to review your changes before merging with the

masterbranch (you can assign a reviewer in the PR page on Github).If accepted (and it passes all necessary checks) you’re new feature will have been merged on Github. Fetch these changes locally.

# git checkout master

# git pull- You have a new master on Github. Pull it to your local machine and the development cycle starts again!

CAVEAT: this workflow is not appropriate for large open collaborations, where fork and pull is preferred.

6.4 Branch naming etiquette

Generally I will start a new branch to either add a new feature git branch feature/cool_new_feature such as for testing or adding a new function git branch feature/sen_function_name. Or if fixing a bug or problem. We should be writing these on the Github issues page for the package. We can then title our branches to tackle specific issues git branch fix/issue_number.

It’s good to push your branches to Github if your working on it prior to it being finished so we all know what everyone is working on. You can simply put [WIP] (Work in progress) in the title of the PR on Github to let people know its not ready for review yet.

6.5 Watermarking

Imagine if someone asks you to reproduce some historic analysis further down the line. This will be easy if you’ve used git as long as you know which version of your code was used to produce the report (packrat also facilitates this). You can then load that version of the code to repeat the analysis and reproduce the report.

As an additional measure, or if you find versioning intimidating, you could watermark your report by citing the git commit used to generate it, as demonstrated below and in the stackoverflow answer by Wander Nauta, 2015.

print(system("git rev-parse --short HEAD",

intern = TRUE))## [1] "ca874b6"This commit hash can be used to “revert” back to the code at the time the report was produced, fool around and reproduce the original report. You also have the flexibility to do other things which are explored in this Stack Overflow answer. This feature of version control is what makes our analytical pipelines reproducible.